Dongsheng Explains No.5

The Belt and Road Initiative at 10: Debt Trap or Development?

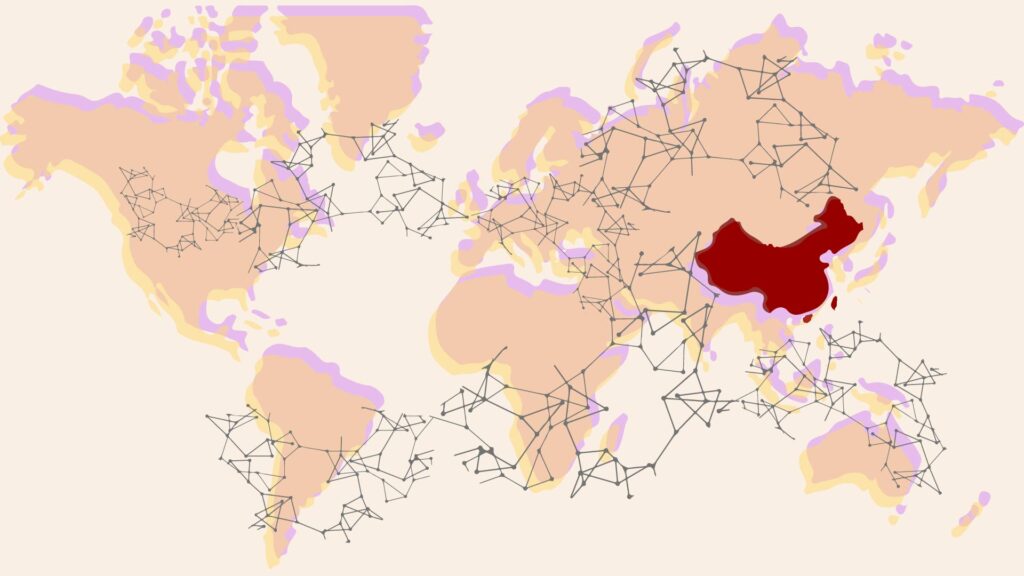

Ten years after its launch in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has emerged as “the largest infrastructure and development project in human history”. An extensive network of agreements demonstrates the global reach and acceptance of the initiative. By 2021, China had forged Memorandums-of-Understanding (MOUs) with 140 countries and 32 international organizations. Notably, 46 of these MOUs were with African nations, 37 in Asia, 27 in Europe, 11 in North America, 11 in the Pacific, and 8 in Latin America. Today, the 151 countries participating in the BRI collectively encompass around over 60% of the global population and their combined economies represent around half of the world’s GDP.

Nevertheless, the mainstream Western media has promoted a narrative of the BRI as having a negative or insignificant impact on the Global South, as part of a scheme to debt-trap these nations. In response to Bolivia’s recent agreement with Russian state nuclear firm Rosatom and China’s Citic Guoan Group to develop its largely untapped resources of lithium – a resource of increasing importance due to its use in rechargeable batteries for mobile phones, laptops, digital cameras, and electric vehicles – US Senator Marco Rubio tweeted: “Whether it’s through China’s BRI, debt-trap policy, or other false promises, nations in our region must remain vigilant of the threat of doing business with Beijing.”

Despite a range of policy makers and researchers debunking Belt and Road Initiative activities as “debt-trapping” – even by World Bank researchers who described the BRI as “largely beneficial” – Western and allied groups have continually stoked fears and misunderstandings of what the BRI is and the role it is playing in the world.

In this issue of Dongsheng Explains, we look at the BRI, its historical development, the implications for the countries involved, and the debt-trap narratives.

What is the BRI?

For over 2,000 years, Eurasia and parts of Africa connected with China through the ancient Silk Road (丝绸之路 sīchóu zhī lù), a network of trading routes that moved goods such as tea, silk, gunpowder, and paper across the regions.

In recent years, the peoples historical aspirations for the routes have been reanimated as the BRI, also known as the One Belt, One Road initiative, a vast infrastructure and economic development project proposed by the Chinese government. Prior to its official launch, two infrastructure-led-development and connectivity projects, launched in the early 2000s, formed the basis of the thinking around the BRI: the Western Development Program to promote economic growth and tackle inequality in western China and the “China Goes Global” policy where state-owned enterprises looked to engage foreign financing and expand their global trade and activities. After decades of industrial development and economic reform, China did not have a fixed roadmap for the next phase of development but rather took the approach of “crossing the river by feeling the stones”.

By 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping officially launched the BRI, which was described as aiming to enhance connectivity and promote economic cooperation between China and countries in Asia, Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. In 2017, after the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, which highlighted the importance of foreign investment, innovation, and cooperation, the BRI, as a flagship project, was elevated. In 2017, its importance was cemented with its inclusion into the Communist Party of China’s amended Constitution in the section covering its objectives around internationalism, described as aiming to build a community of “shared interest” and to achieve “shared growth” through “discussion and collaboration”.

The initiative is named after the “Belt,” which refers to the Silk Road Economic Belt, and the “Road,” which refers to the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, each pointing to its land-based and maritime components. With the aim of overcoming obstacles to development and raising the productivity of societies in many regions of the world, the BRI seeks to revitalize and expand on the concept of the Silk Road through the construction of infrastructure and industrial manufacturing capacities. In Africa alone, between 2000–2020, China built more than 100,000 kilometers of roads and railways, around 1,000 bridges, nearly 100 ports, and more than 80 large-scale power facilities, as well as 130 medical facilities, 45 sports venues, and more than 170 schools.

It also includes the promotion of trade and investment among participating countries and the development of economic corridors in contrast to only building conventional economic unions and zones – such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (valued at US$62 billion), which connects Gwadar Port in Pakistan to China’s northwestern region of Xinjiang. The significance of economic corridors lies in how they, as the Asian Development Bank puts it, “provide important connections between economic nodes or hubs that are usually centered in urban landscapes” and the “network effects they induce”. In principle, all of this strengthens regional connectivity and integration not only between urban and rural spaces, but between historically “central” and “peripheral” regions.

For the Global South who remain underdeveloped due to the colonial and neocolonial global financial systems, the BRI’s main goal of poverty alleviation – especially given China’s recent eradication of extreme poverty – confronts pressing needs. The BRI has proposed to accomplish this through the multiprongs of enhanced connectivity, trade and investment opportunities, regional economic integration, infrastructure development, technology transfer and knowledge sharing, cultural exchange, and people-to-people connectivity.

What does the BRI mean for China?

The Belt and Road Initiative is a significant foreign policy project of China. It aligns with the principles of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics as demonstrated in four ways.

Firstly, it is a manifestation of China’s long-term planning and strategic vision and the broader goal of promoting social stability, economic development, and cooperation with other countries.

Secondly, the BRI is driven by the Chinese government, reflecting its active role in state-led development and its emphasis on strategic infrastructure investments.

Thirdly, the BRI incorporates elements of both planned and market-driven economic approaches. While the Chinese government provides funding and support for many projects, private Chinese companies also participate in the BRI initiatives, contributing to the development of a global network of economic cooperation and trade. A driver behind this was that, after a decade in the World Trade Organization, China accumulated a huge trade surplus, and after the 2008 financial crisis (when China bought hundreds of billions of US bonds), Beijing had a massive amount of dollars that could be invested abroad. This provided Chinese companies – especially SOE’s, funded by China Development Bank, China Eximbank etc. – with an important source of foreign reserves for investment capital, enabling them to expand trade globally.

Lastly, the BRI reflects China’s emphasis on global cooperation and its aspiration to increase its contributions to international diplomacy, in line with the principles of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. This is evidenced by the investment in government administrative infrastructure – such as either building or refurbishing parliaments in at least 15 African countries, including the Republic of Congo, Liberia, Mozambique, the Seychelles, and Guinea Bissau. The diplomatic implications are also evidenced by some of China’s infrastructure-driven security approaches with the construction of public infrastructure in regions that suffer from internal instability and conflict – such as in the case of the China-funded, US$329 million Ethio–Djibouti Transboundary Water Project, designed to bring fresh water to over 700,000 people in Djibouti.

Is the BRI an effective strategy towards development?

The world lags behind the goal of achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, as few states have been able to meet their financial obligations and the so-called “Developed Nations” refuse to contribute anything substantive; the poorer countries would require at least an additional $4 trillion in investment per year to do so.

The options provided by the West through the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have been exhausted. New proposals – most of which seem to frame their projects in competition rather than collaboration with China – like the US’ Build Back Better World (recently repackaged as the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment) and Europe’s Global Gateway have not shown substantive results – the later has even been described as a “failure” by Western foreign policy analysts.

Though there is a view that assessing a project of this scale after a decade sets certain limitations on quantifying its impact qualitatively, the BRI has clearly impacted global development, both materially and conceptually. This is particularly important for the Global South, where centuries of colonial and neocolonial policies of underdevelopment have left countries with untarred hazardous roads, little-to-no public infrastructure, and few sources of energy supply and generation; what Guyanese political thinker Walter Rodney described as “a product of capitalist, imperialist, and colonialist exploitation” where countries of the Global South were taken over directly or indirectly by the Western capitalist powers. “When that happened,” he explained, “exploitation increased and the export of surplus ensued, depriving the societies of the benefit of their natural resources and labor.”

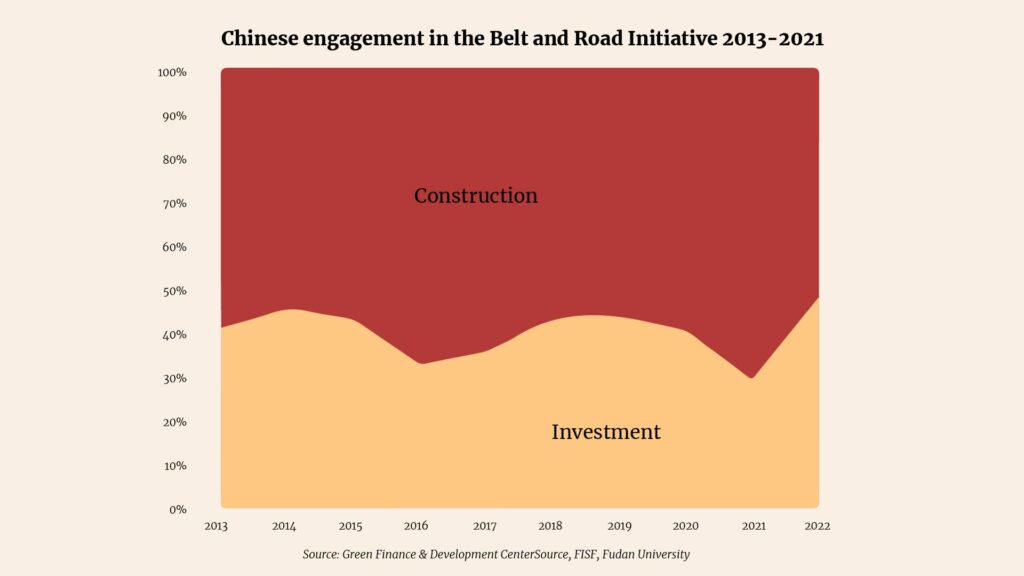

The BRI strategy has shown significant success, supported by compelling data. Though investment dropped over the pandemic years, since it began in 2013, BRI projects have totaled US$962 billion, with more than half (US$573 billion) going to construction contracts, and the rest (US$389 billion) spent on non-financial investments. The impact of the BRI on China’s outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) has seen a dramatic increase where China’s outbound FDI has almost doubled between 2012 and 2020 to US$154 billion, securing China’s position as the world’s leading overseas investor. By September 2021, China’s total trade value with BRI partner countries increased to US$10.4 trillion. Today, it is estimated that there are more than 1,700 BRI projects completed or in development.

Much like global development trends, there are areas that can be improved. For example, though projects engaged in renewable energy (solar, wind, hydro) increased by 50% in 2022, fossil fuels constitute 63% of Chinese BRI energy engagement abroad.

Is BRI indebting the Global South?

Widely peddled by Western media and politicians as the main impact of the BRI in the world, the debt-trap narrative obscures certain facts, the first being that many participating countries in the BRI came to it locked in Western-issued debt incurred not only by decades of borrowing almost exclusively from Western lenders, but debt incurred from several mechanisms of colonial expropriation and extraction. The wealth of international financial institutions and Western countries comes from centuries spent economically exploiting the countries and people through colonialism and then through the set up of financial mechanisms (particularly during the 1980s Structural Adjustment Programs) that have maintained and deepened unequal economic relations rather than solve them. If we understand the concept of debt trap where a country accumulates unsustainable levels of debt, often due to borrowing large sums of money from another country or international financial institutions, then the accolade more accurately goes to the West.

While China is the African continent’s biggest bilateral creditor, most of Africa’s total public debt is held by private Western creditors. Out of sub-Saharan Africa’s overall public debt, which stands at US$945 billion, Chinese entities hold only 8%, equivalent to US$78 billion. Half of Africa’s public debt is domestically issued, while the other half is owed to external actors, totaling US$427 billion. Among these external actors, China accounts for 18% of the debt. The remaining one-third of the debt is divided between bilateral official partners, international finance institutions, and Eurobonds, each contributing an equal share.

The approach and goals of Chinese funding has a different quality. Unlike IMF financial agreements, Western commercial investment, and overseas development assistance, Chinese funding does not come with constrictive conditionalities. Western lenders have and continue to propose rigid, austere conditions – such as privatization of the economy, commodification of public resources, and deregulation of economic activity of private international capital – that undermine the sovereign development of countries.

Lastly, evidence of more favorable terms comes in the various agreements signed by China, but more than that, it comes from China’s theory of patient capital. Previously having been adopted within the boundaries of China, it has gradually emerged as a major investor outside its territory, with the China Export-Import Bank and China Development Bank being major participants. The loans that these state agencies provide are long-term investments and are not on short repayment schedules. These loans are given to release infrastructure bottlenecks and, in so doing, support social development. Borrower countries are given flexibility (from restructuring loans to writing-off interest free loans), as benefits are forecast to come in the long-term. For example, prior to investment, it was known that 30% of the investment in Central Asia and 80% of the investment in Pakistan would not be recovered.

In 2021, China pledged to redistribute US$10 billion, or 23% of its IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDR) to African countries compared to US$100 billion or 20% of SDR redistribution to emerging markets committed by other G20 countries, such as France, Italy, the US and the UK. The difference in priorities is clear: China is only one country (US$ 33 trillion GDP PPP) while the G20 includes the 19 largest economies (combined GDP US$100 trillion GDP PPP) in the world.

What is next for the BRI?

The Third Belt and Road Forum in 2023 will reportedly be held in September this year. The previous forum held in 2019 had 200 countries participating and concluded with deals being signed worth more than US$64 billion. Though predictions of what will happen this year vary due to the stagnation of finance and investment seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, that went from US$68.7 billion in 2021 to US$67.8 billion in 2022, some policy researchers believe this might see the project rebound and revitalized, particularly due to a “strong Sino-Russian geostrategic partnership” that has arisen within recent shifts in the global geopolitical landscape. With nations queuing to join BRICS, new regional vehicles gaining traction, the proposal of complementary initiatives such as the Global Development Initiative (2021), and Global South nations having become significantly involved in Chinese diplomatic and economic relations, the BRI forms part of a different set of geopolitical and socio-political aspirations that are already altering the international order that favours a Global South-led world system.

Ten years after its launch, the BRI represents an alternative platform (outside of the US-led West), that has not only assisted individual countries to develop but has catalyzed stronger regional and multilateral formations, more independent of lines drawn by colonialists or supervision by the West under ill suited models. Creating alternatives for much-needed finances, political leverage, and regional integration prospects, projects like the BRI serve to mitigate some of the ill effects of neoliberal economics – in so doing, “loosen the screws” of the global financial system in which the West trapped much of the world – while opening up more room for the Global South to contemplate and build alternative paths to development.

Subscribe. Dongsheng Explains is published monthly in English, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Follow our social media channels:

- Twitter: @DongshengNews

- Telegram: News on China

- Instagram: @DongshengNews

- YouTube: Dongsheng News

- Facebook: Dongsheng News

- TikTok: @dongshengnews