Dongsheng Explains No.3 | May 2023

Is China’s housing market in trouble?

In recent years, China’s housing issue has been prominently featured in the Western media. Rapid urban development, skyrocketing prices, the dependency of local governments on land revenues, and the most “shocking”, the rumored bankruptcy of the real estate giant Evergrande, 13 years after the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007-2008 shook the world economy, aroused the attention of financial analysts everywhere. However, what is the actual situation of the real estate market in China and what is the government doing?

How has the housing question been addressed historically?

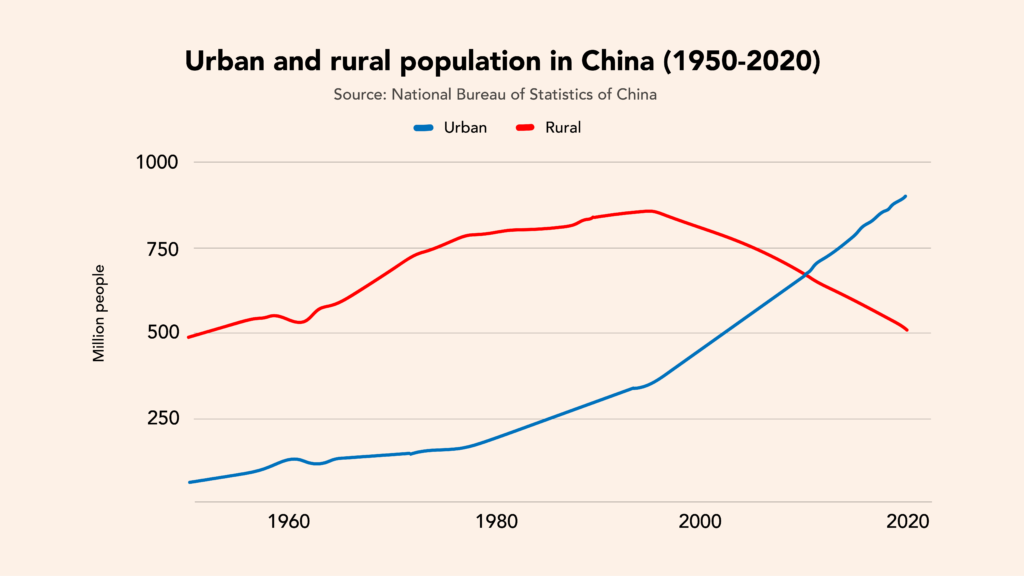

When the Chinese people, led by Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China (CPC), founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, it was amongst the poorest countries in the world. In 1950, only 10 countries had lower per capita GDPs than China, and only 11% of its 552 million people lived in urban areas. As industrial development increased, the cities also grew rapidly. Particularly after the reform and opening up, migration from the countryside to the cities became a constant social phenomenon. By 2022, China’s urban population had expanded to 921 million, accounting for 65% of the total population.1

Moreover, the number of cities with over 1 million people has grown from 90 in 2000 to 167 in 2020, while urban areas of less than 1 million have fallen from 172 to 130, suggesting that the population has concentrated in bigger urban centers.2

The combination of a massive population with a growing income and the boom of the urban areas has significantly driven housing development, which has undergone great changes since 1949.

Soon after the establishment of the PRC, urban land was nationalized and housing was withdrawn from circulation. For more than 30 years, China had a socialist welfare housing system, where housing units were built and managed by government agencies, public institutions, or state-owned enterprises (SOEs), etc. In the early 1980s, 75% of urban households in China lived in public rental housing.

With the reform and opening up, the Chinese government decided to develop the real estate industry. Beginning in 1978, the State’s investment policy began shifting from a single State budget to the joint investment of the State, enterprises, and individuals. This new policy spurred development in the housing market, most notably after 1992 when the socialist market economy was established. By 1997, 9.64% of total social fixed asset investment was in real estate development. The urban housing market gradually formed and the living conditions of residents improved significantly, with the per capita housing construction area increasing from 6.7 square meters in 1978 to 17.8 square meters in 1997.

Since 2008, economic growth has slowed and the real estate sector has faced adjustment. During this period, the government has paid more attention to the role of macro-control policies such as taxation and attached great importance to the construction of subsidized housing to meet the needs of low-and-middle-income people. The massive scale of China’s housing market is still present, but its growth has slowed down.

Who is running the real estate development in China?

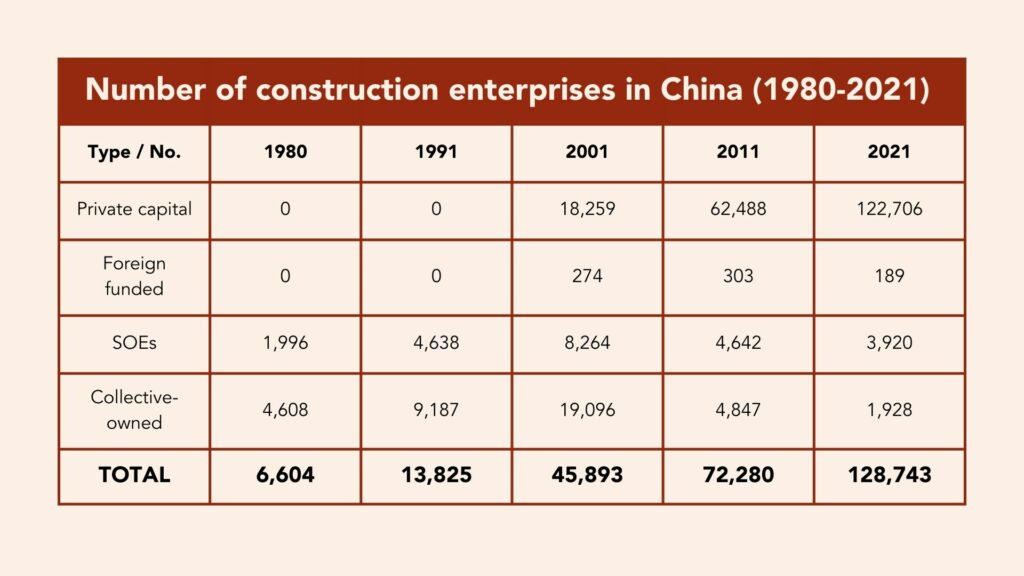

With the formation of the socialist market, private capital in the real estate industry increased quickly. In 1993, there were only 505 private construction companies in China; this grew to 18,259 in 2001 and more than 122,000 companies by 2021. Gradually, public and collective ownership of construction companies was substituted by private capital. By 2021, private capital, both foreign and domestic, accounted for 86% of the gross value added in construction, totaling 25.2 trillion yuan (US$ 3.9 trillion), and accounted for 89.6% of the 52.8 million people working in construction.

Collectively owned companies, which are township-based units, owned by the villagers and managed by a villagers’ committee, peaked at 29,872 units in 1997 and has decreased since then.

What is the relationship between the real estate industry and local governments?

Since 1953, rural land ownership has remained collective, while urban land ownership has remained public. Since the 1990s, local governments could “sell” (transfer) the right to use the land to qualified entities. Revenues generated from this practice, such as land-related taxes and income from state-owned land transfers, are now commonly known as “land finance”, which accounted for 89% of the local public budgetary revenues in 2018.

Professor Zhao Yanjing points out that local governments use the land finance to invest in infrastructure and enhance public services, which increases land value. The government spends the income from land finance on urban construction, such as utilities development, roads, hospitals, and schools, thus turning suburban land into new urban areas. As urban construction expands, housing prices rise, pulling land prices up as well.

In 2019, China’s urban home-ownership rate reached 96%, one of the highest in the world, compared to the US’s 64.2% and Japan’s 61.9% in 2017. For Brazil and South Africa, that rate was 72.5% and 69% respectively. Among the home-owning households in China, 58.4% owned 1 property, 31% owned 2 properties, and 10.5% owned 3 or more properties. High demand for housing, particularly in large metropolises where housing shortages worsened, has served to push house prices even higher. At the same, many smaller cities and rural areas have housing surpluses as a result of people moving to larger cities and leaving many new housing developments empty, estimated today at 50 million vacant housing units. According to Beike Research, the average housing vacancy rate surveyed was around 12% in 2022.

How is the government addressing the problems in this industry?

The trigger for the 2007-08 financial crisis was the bloated housing market, especially in the Global North, (not only in the US, but also in Britain, Spain, Ireland, and other countries), a result of pushing mortgages even to consumers who would obviously not be able to pay them back. Not only did the so-called sub-prime mortgage market, which had reached entirely unrealistic values, collapse, but, because these mortgages had been packaged into derivative products in financial markets in such forms as collateralized debt obligations and collateralized loan obligations, this collapse brought, in its wake, the collapse of other financial markets and left many banks and other types of financial institutions facing disaster. However, the Chinese State will not allow that type of financial speculation; it is attempting to avoid a bubble and prevent a crash as opposed to banking bailouts after the crisis breaks out.

In August 2020, amid a mature real estate market, the Chinese government issued the regulation known as the “three red lines”, which provide three key indicators of the financial health of real estate developers. The regulation caps these companies’ ratio of debt to cash and equity and assets, and promotes sustainable growth of the sector. The government called on companies to reorganize their finances by 2023, classifying them as “green” if they meet these healthy-finance criteria and thus allowing them access to new credit.

Evergrande, the second largest real estate developer in China, garnered the most attention. By December 2020, the Evergrande Group’s debt had accumulated to US$300 billion, and its liability-asset ratio was 84.7%, above the 70% established in the three red lines.3

As the company was struggling to pay back its debt, and in order to avoid misuse of the funds, two local governments took control of Evergrande’s revenue, and since August 2021, eight other provinces have requested that Evergrande place pre-sales revenue into custodial accounts as the cash-strapped developer put hundreds of unfinished projects on hold. The Chinese government is taking control of the company’s revenue and resolving the issues before a debt crisis explodes.

The 5% cap on the annual growth rate of rent increases improved the living conditions of all Chinese households and further slowed the otherwise explosive price hikes. The bottom line of the regulation is that, as president Xi Jinping said at the 19th CPC National Congress, “houses are for living, not for speculation.”

Besides controlling price speculation, the Chinese government has promoted a series of policies for the development of social housing in order to facilitate and ensure access to housing for the younger generations and those with lower purchasing power. The Xiamen government, in Fujian province, reduced the market price by 45% of 4,000 apartments. The Henan government bought 1,050 flats from Evergrande, whose construction was interrupted due to its liquidity issues. In general terms, the Chinese government is supplying 6.5 million new low-cost rental housing in 40 major cities, which started in 2021-2025, to ease housing difficulties for 13 million young people; tier-one cities like Beijing and Shanghai will supply a total of 1.87 million units of low-cost rental housing. In 2021 alone, 936,000 units provided housing for 2 million young people in 40 cities.

Slowing housing demand, a result of uncertainty during the pandemic and increased geopolitical tensions, and these new regulations, restrained some speculative behavior in the market. The profitability of these real estate developers was impacted; but as their business model is based on indebtedness, while fruitful during fast market growth, as the sector matures, it can represent a serious risk for the system.

Amid the slowdown of the Chinese economy in 2022, the government eased a series of measures, and provided economic stimulus to the real estate sector: postponing the deadline for the assessment of the three red lines, extending the deadline for the banks to reduce their ratio of outstanding mortgages and property loans to total loans, and cutting China’s mortgage interest rates.

In the wake of this stimulus, after 18 months, housing prices are increasing; this can be seen as a sign of a recovery of the demand in the previously depressed market. Nevertheless, property investment in 2022 fell by 10%, and 5.7% in the first two months of 2023; land “sales” plunged by 29% in the first two months of this year, after a drop of 53% in 2022, suggesting that the real estate sector will need more time to return to steady growth.

Conclusion

China’s housing market moved on a parallel path with the overall economy: at unprecedented speed and scale. Its development, however, has reached a more mature stage in recent years and it is struggling to maintain previous growth rates. The government controls enacted to stabilize the financial security of real estate developers, the brake on speculation, and the development of indemnificatory housing projects for low-income groups and young first-time home buyers, aim to treat real estate as the people’s rights to both housing and sharing in the fruits of development, and came at a crucial point. The Chinese government has shown flexibility in allowing companies “to breathe” amid a tough market. However, they aren’t willing to allow speculation in the long term, especially when, due to its size, it could lead to devastating shocks in the overall economy. This process should lead to a more sustainable business model, less speculation in housing, and the elimination of the “rotten fruits” in China’s immense real estate sector.

- This rate is still lower than that of developed countries such as South Korea (81%), US (83%) or Japan (92%), and also lower than developing countries such as South Africa (68%), Mexico (81%), Brazil (87%) or Argentina (92%).

- In China, statistically, “urban areas” include cities and towns whose basic authorities are residential committees; while “rural areas” include townships and villages that are based on villagers’ committees.

- Very low values of this ratio indicate that there is idle capital, and very high values indicate excessive indebtedness.

Subscribe. Donsheng Explains is published monthly in English, Spanish and Portuguese.

Follow our social media channels:

- Twitter: @DongshengNews

- Telegram: News on China

- Instagram: @DongshengNews

- YouTube: Dongsheng News

- Facebook: Dongsheng News

- TikTok: @dongshengnews