Dongsheng Explains No.6

How is China ensuring food security for 1.4 billion people?

Although pandemics, extreme weather events, and geopolitical conflicts have led to disruptions in food supply chains and rising international food prices, there is no shortage of food for the world’s population. However, hunger continues to affect millions of people. According to the latest State of Food Insecurity and Nutrition in the World report, between 691 and 783 million people will go hungry in 2022. This is 9.2 per cent of the world’s population and 122 million more than in 2019.

The 1.4 billion people on the African continent, despite having 60% of the world’s arable land, face increasing food insecurity and severe famine. So how has China managed to produce approximately 25% of the world’s food, using less than 9% of arable land and 6% of fresh water to feed a population equivalent to that of Africa’s?

In this Dongsheng Explains, we explore some of the social, historical, and economic policies and realities that underpin China’s ability to feed its people, provide some stabilization of the global food market and continue to contribute to eradicating global food insecurity by feeding one-fifth of the world’s population.

How did the communist movement address the agrarian question?

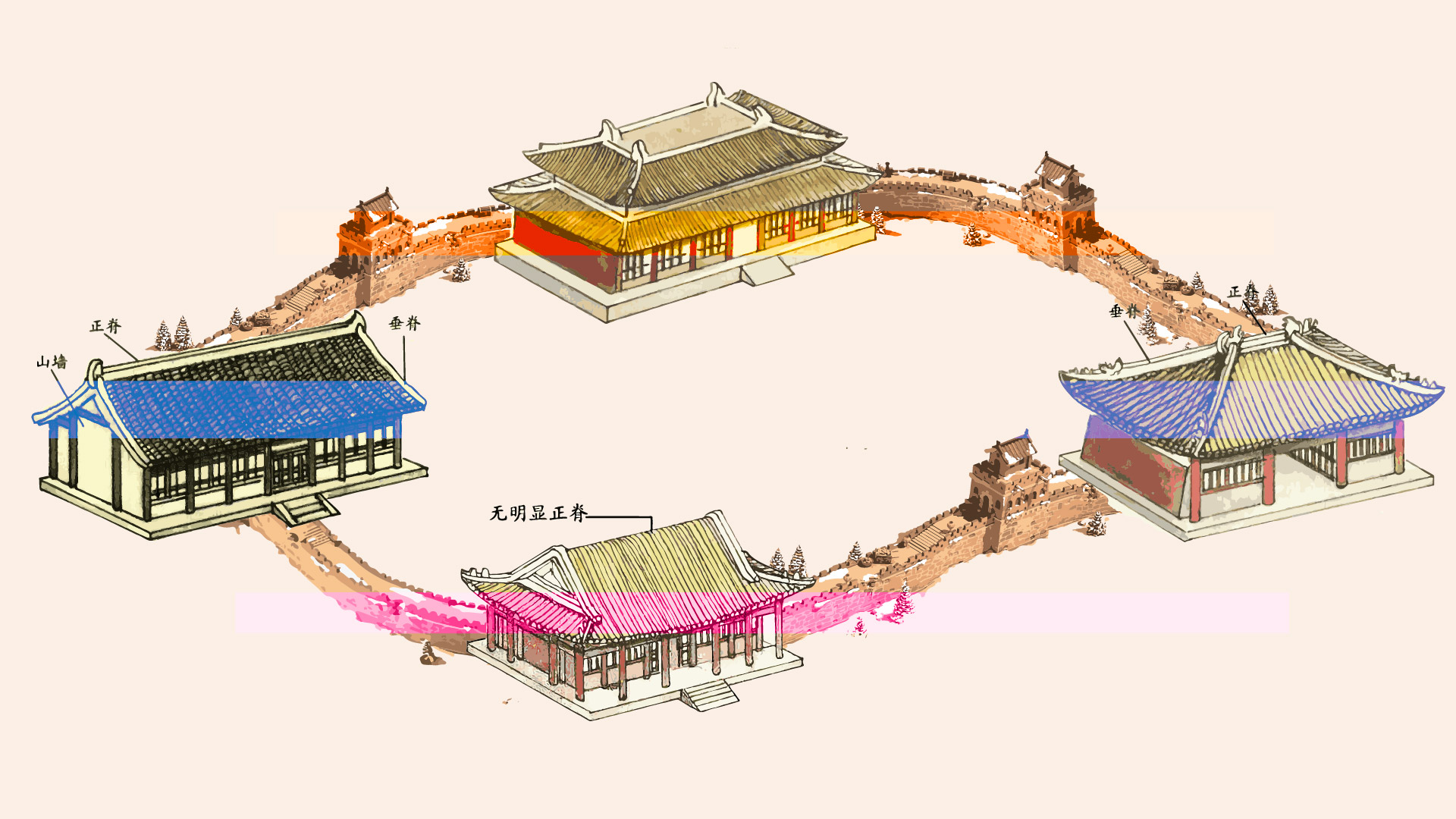

China is a nation with millenia-old agricultural traditions, where the peasantry has always played a leading role. Because of its size, tensions in the land/population ratio determined the stability, the rise and fall of several dynasties; often was the case that the first national policy of a new dynasty focused on land redistribution and lowering taxes.

By the late 19th century, the Qing dynasty had been unable to stop abuses by foreign powers. Since 1840, opium wars, Sino-Japanese wars and unequal treaties raise the curtain of “Century of Humiliation” and China’s territory was divided into military cliques controlled by Chinese warlords, which deepend the structural dependence of peasants on the landed gentry class. Compounded by natural disasters, this crisis led to a drastic decrease in resources, resulting in class polarization, famines, and peasant rebellions.

Mao Zedong, in his Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society (1926), described the vast majority of the Chinese population as the poor, semi-owner peasantry who compensated for the deficit by “renting land from others, selling part of their labour power, or engaging in petty trade”. The Communist Party of China (CPC) consolidated around these contradictions and began to organize the peasants, gaining enormous support in rural areas of the country. Addressing the agrarian question became one of the main goals of the Chinese Revolution, and even before coming to power, it began a process known as the Land Reform (土地改革 pinyin: tǔdì gǎigé) to confiscate land from landlords and return it to the peasantry.

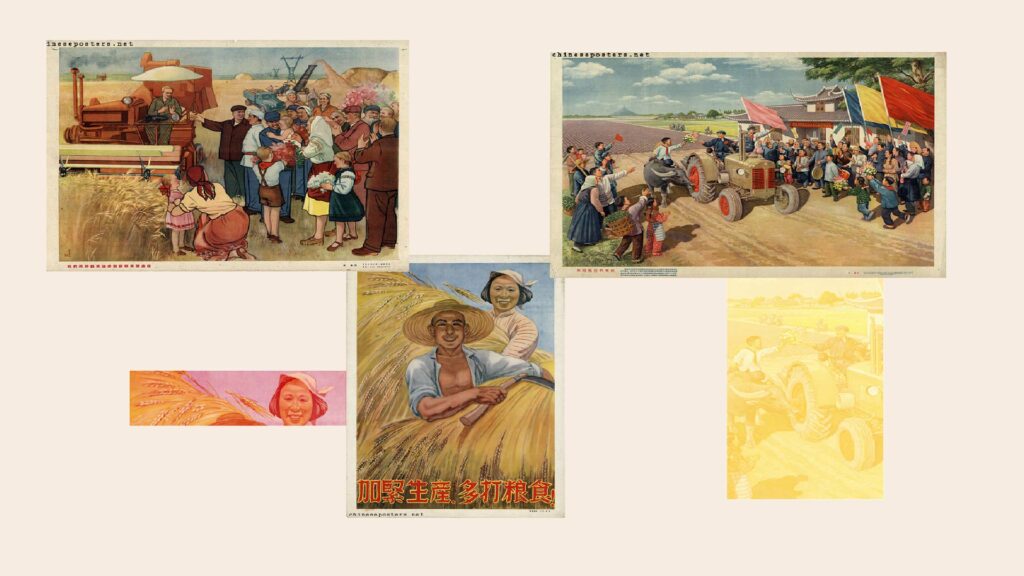

In 1949, finally in power, the CPC set among its main challenges to end hunger and increase the productive forces. To this end, in 1950 it promulgated the Land Reform Law (土地改革法 tǔdì gǎigéfǎ) to put an end to private land ownership, abolish the feudal production system, guarantee the right to peasant property, and unify the criteria for its distribution. From this, 47 million hectares of land was allocated to more than 300 million peasants throughout the country. With the available land per family being relatively small (approx. 0.5 hectares), the government promoted the Mutual Aid Groups and, later, the Agricultural Cooperatives, to encourage cultivation on a larger scale and to collectivize some of the tasks of production.

During the first nine years of the People’s Republic, agricultural production grew at an average annual rate of 7%, from 113.2 to 200 million tons, allowing for an increase in per capita grain consumption from 209 to 303 kgs. Even so, there were still problems of low productivity, lack of technology, and shortage of financing. The national industry had been devastated by decades of war and tool production capacity was reduced to small workshops producing sickles, hoes, and shovels. Practically all agricultural work was manual.

In the First Five-Year Plan (1953–1957), among the 156 major construction projects in the country was the construction of the first domestic tractor manufacturer. Its construction began in 1955 and was completed in 1959, and was based on Soviet technology. In the same period, the now renowned YTO group and the Chinese Academy for Agricultural Mechanization Sciences were founded.

China was still a poor and economically underdeveloped country, with huge regional imbalances, a huge and rapidly growing population, and an agricultural production that still did not meet the demands of the population and industry. In 1958, the government promoted the creation of the rural People’s Communes (人民公社 rénmín gōngshè), which completely collectivized agricultural production and replaced the agricultural cooperatives in the task of planning and maintaining the work unit.

Between 1959–1966, agricultural production fell sharply to 143 million tons in 1960, and it took six years to recover to the 1958 level. The government promoted technological development as the way to overcome the harsh situation. In 1963, at the Scientific and Technological Work Conference in Shanghai, Zhou Enlai set out the goals of the “Four Modernizations” (四个现代化, sì gè xiàndàihuà), which included the agricultural sector, and called on science professionals to contribute to its realization.

Heeding this call and sensitized by the unstable production of food in his country, the agronomist Yuan Longping had started working on improving rice productivity. In 1973, he succeeded in growing the world’s first hybrid rice, a variety that produced 20-30% more than conventional rice. By 1976, it was already massively cultivated. This was a momentous event for agriculture not only in China, but worldwide.

What was the basis for the recent modernisation of agriculture to achieve food security?

Until the end of the 1970s, policies affecting food security were limited to organizational changes, the relative price system, and partial liberalization of the commodity market.

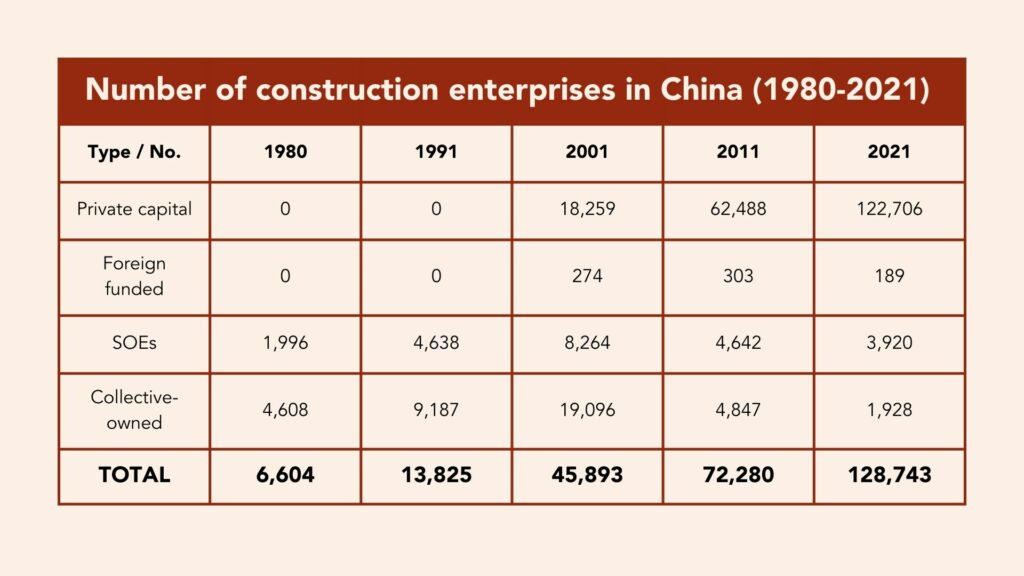

After the beginning of the Reform and Opening-up period, more significant modernisation measures were adopted, and particularly in the agricultural sector, management through People’s Communes was replaced by the Household Responsibility System (家庭联产承包责任制 jiātíng liánchǎn chéngbāo zérènzhì). Collective land was reallocated to individual rural households and they were given relative autonomy over use decisions and crop selection. In the first period (1982–1984), families were allowed to own, use, benefit from, and dispose of (except for sale) the land for periods of up to 15 years, and then, from 1994 onwards, for up to 30 years. The aim was to give a guaranteed return on long-term investments made by the families to improve the land and production.

During this period, great efforts were made to attract technology and foreign investment, as well as create incentive programmes to increase agricultural production. Reforms in the countryside in the first half of the 1980s had positive effects on agricultural production, but soon problems of functionality arose, as the policy of high prices for agricultural products and consumption subsidies led to a deficit in the government budget.

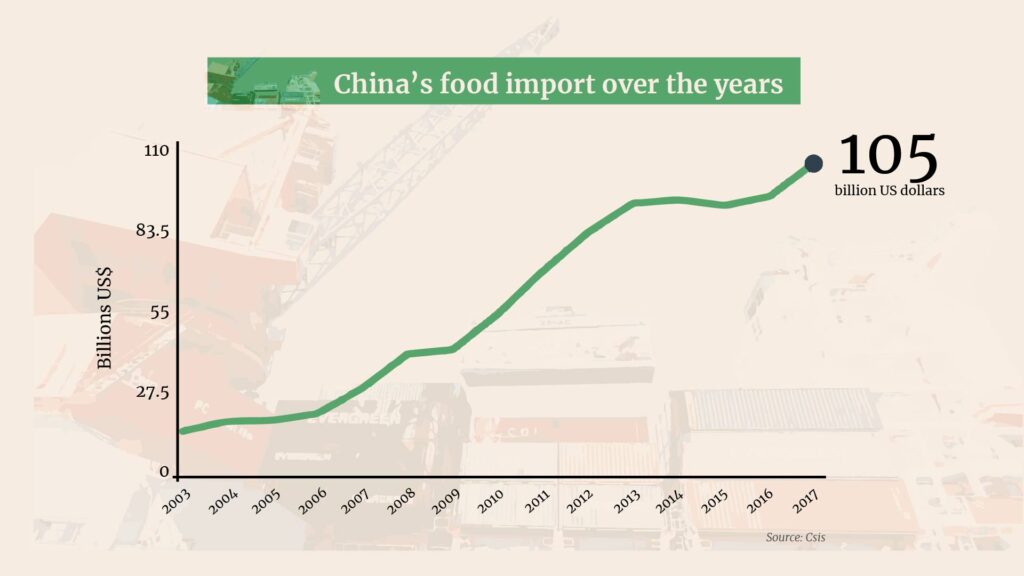

During this period, China’s opening up and integration into world markets was seen as a necessary tactic, but it also brought with it numerous challenges and contradictions. Since its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has gradually opened up its agricultural sector, and the commercialization and internationalization of agriculture in China has increased dramatically. According to the WTO itself, in 2004, China became a net importer of agricultural products. This had serious consequences for domestic production (mainly of soybeans) and generated a very high dependence on very few countries.

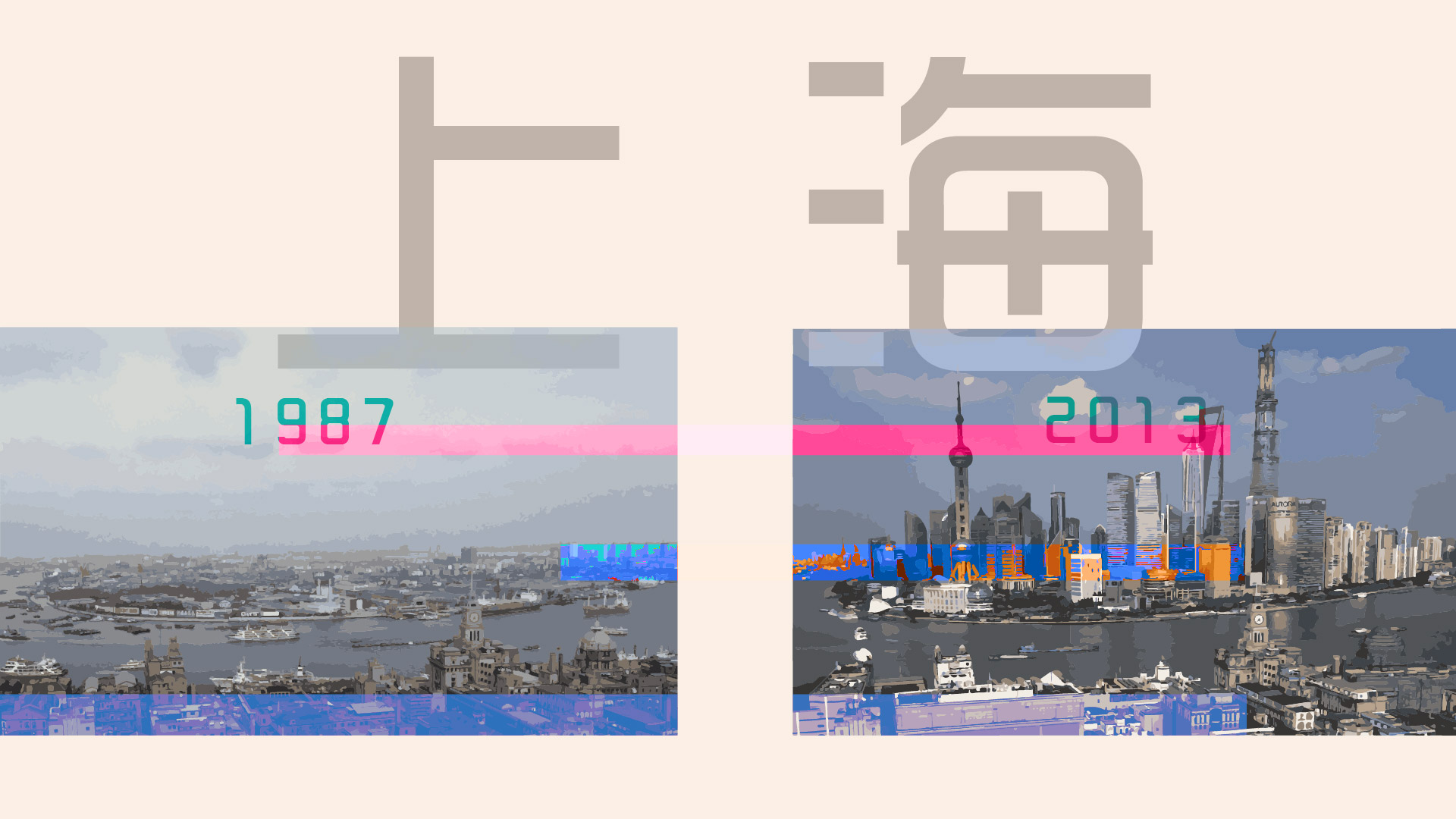

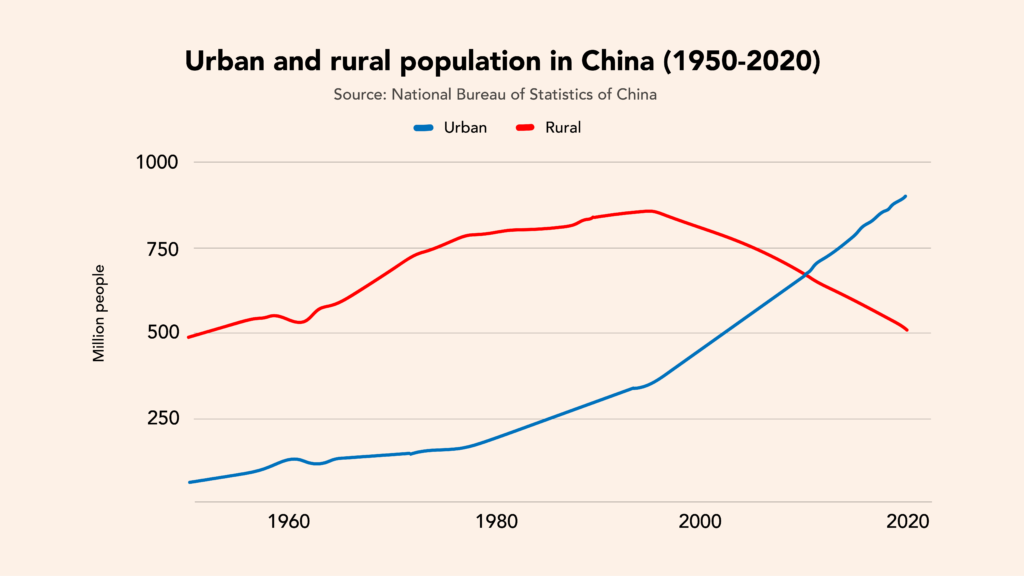

Another challenge in this period had to do with land-use changes. The territory demanded for industrialisation and urbanisation of the countryside generated strong competition for arable land. From the 130 million hectares surveyed in the 1996 Agricultural Census, the figure fell to 121.6 million by the end of 2008.

What are the latest developments in Chinese agriculture?

China’s agricultural policies in recent decades have evolved to prioritise objectives beyond mere food production, such as increasing farmers’ income, ensuring food security, and improving environmental performance. Beginning with the 2018 adoption of the strategic plan called “Rural Revitalization” (乡村振兴 xiāngcūn zhènxīng), China has stepped up modernization of the agricultural sector and industrialization of rural areas to create economic opportunities that help narrow the gap between rural and urban dwellers.

On such efforts were the 2004 agricultural policies aimed at improving food security, which involved measures such as the elimination of taxes for more than 800 million rural farmers. In addition, the government increased direct subsidies by 10 per cent, totalling 11.6 billion yuan, to support the grain production of 600 million farmers in 29 provinces.

Another example of efforts to improve agricultural efficiency and food self-sufficiency as a national priority was the 2008 approval of measures to advance rural reform and development. The measures enabled 700 million peasants to sell, rent or mortgage their land, while property rights were not altered and the land remains collectively owned. This opened up the market for agricultural land-use rights transactions, which allowed peasants to earn an income to use for other activities, and buyers to increase the scale of production. To avoid the decrease of area devoted to production, the regulation also defined that land may never be used for non-agricultural purposes, which guaranteed at least 120 million hectares devoted to agriculture.

The protection and expansion of farmland is a central government priority for food security, so in addition to maintaining the “arable land red line” of 120 million hectares, the country invested in the construction of high-level irrigated farmland. In June this year, it issued 19 billion yuan in special financial bonds to support the construction of such land. Since 1949, China quadrupled the irrigated area, which by 2022 reached 68.6 million hectares (more than half of the agricultural area) and was responsible for producing three-quarters of its grain production and more than 90 per cent of cash crops.

Another of China’s central agricultural policies is its strategic plan for the revitalisation of the seed industry. China is virtually self-sufficient in wheat and rice seeds, but not in soybeans and maize, mainly because the average yield of China’s soybean and maize varieties is only 60-70% of the yield of fields in the United States. Experts indicate that the contribution of improved seeds to yield increases in China is only 45%, leaving much room for improvement from the level of more than 60% in developed countries in the West. Aiming to narrow these gaps, the government proposed a review of regulations governing genetically-modified crops last November.

Advances in agricultural mechanisation are also responsible for China’s increased self-sufficiency. The country went from building its first tractor in 1955 to having more than 8,000 companies producing agricultural machinery and equipment by 2022, 2,200 of which exceed 311.6 billion yuan in business revenue. Domestic manufacturing has basically covered all categories and can produce more than 4,000 kinds of agricultural machinery. Since the founding of the country, the mechanisation rate of agriculture has grown 70 times. In 2022, the subsidy policy for the purchase and application of agricultural machinery enabled farmers, agricultural production, and management organisations in purchasing more than 3.8 million sets of agricultural machinery from more than 4,000 domestic enterprises.

Scientific and technological developments have also played an important role in this regard. The information infrastructure in agriculture and rural areas has been modernised gradually but significantly. Modern information technologies, such as the Internet of Things, satellite remote sensing and big data, have been popularised and applied in the sowing and breeding industries, and significant results have been achieved in crop rotation and fallow monitoring, remote diagnosis of animal and plant diseases, precise operation of agricultural machinery, drone flight control and precise feeding, etc.

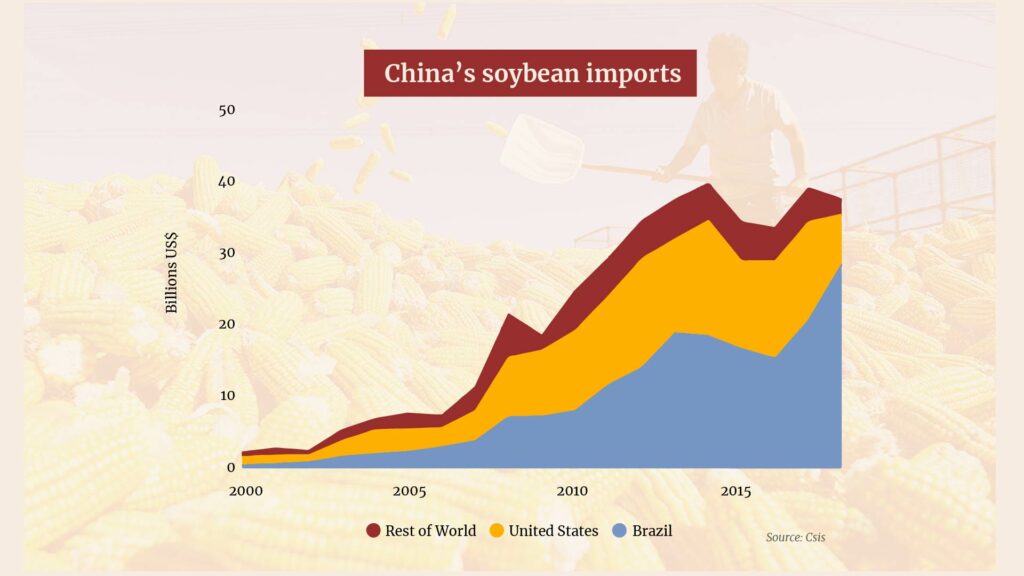

Finally, the war in Ukraine and the escalation of tensions with the United States significantly reinforced the government’s priority on grain self-sufficiency. Although it is completely self-sufficient in soybeans for human consumption, the country imports more than 80% of the soybeans it uses for animal feed and oil, with Brazil being the largest source of imports with almost 60% in 2022, while the US ranks second with 32.4%. As for maize, China imported 20.6 million tonnes last year, equivalent to 7.4% of domestic production, and according to customs data, 72% of supplies came from the US. In 2021, imports of this cereal reached a record 28.35 million tonnes, with 70% coming from the US and 29% from Ukraine.

Efforts to reverse this situation are numerous, such as the aim of increaseing the area under soybeans and oilseeds by 666,000 hectares this year; reducing the share of soybean meal in animal rations from 14.5% to 13% by 2025; providing subsidies for the production of these grains; and diversifying supplier countries, prioritising BRICS countries. In the medium term, according to a report by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the country plans for the self-sufficiency rate of maize to reach 96.6% by 2032, which would reduce annual imports to 6.85 million tonnes. In soybeans, according to April announcements, the country aims to increase domestic soybean production by 75 kg/ha this year and will use soybean productivity as a yardstick for judging officials’ performance.

How has China dealt with hunger and nutrition?

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, comprehensive food productivity has experienced a dramatic growth, making the historic leap from chronic shortages to a basic balance between supply and demand. Total national grain production increased six-fold from 113.2 million in 1949 to a record 686 million tonnes in 2022. Per capita food holdings are 483 kilograms, higher than the internationally recognised food security line of 400 kilograms.

Between 2000 and 2017, China significantly reduced undernourishment, with the affected population falling from 16.2 per cent to 8.6 per cent. This progress was facilitated by a substantial increase in annual per capita income from US$ 330 to US$ 9,460 in the same time period. In particular, China was responsible for two-thirds of the overall decline in undernourished people among Asian nations from 2010 to 2017.

This has been made possible in large part by China’s targeted poverty alleviation initiative, which succeeded in lifting nearly 100 million people out of extreme poverty by 2020 by adopting an integrated, multidimensional approach to food security. China’s current rural revitalization strategy is a continuation of efforts to improve rural areas and rural life, and to secure the supply of agricultural products, cereals in particular.

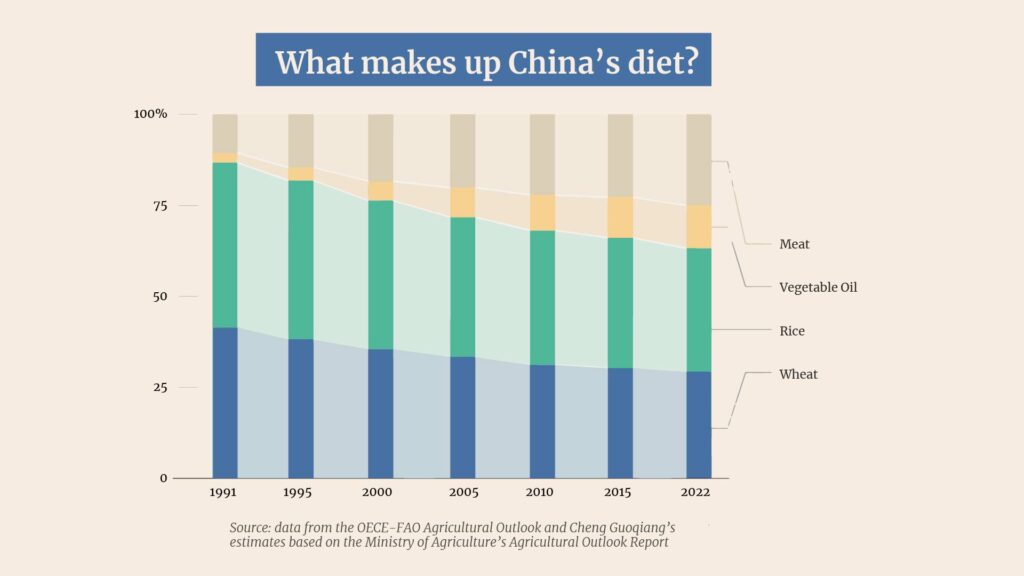

The economic development that China has experienced in recent decades has, for better and for worse, brought about changes in people’s diets. In rural areas, studies show that children have experienced remarkable growth thanks to access to more nutritious and healthier food. In particular, 13-year-olds grew by an average of 7.5 cm and gained 6.6 kg from the average of a decade ago. Moreover, among the 200 countries and territories surveyed, China recorded the largest increase in male height globally between 1985 and 2019. Meanwhile, in more developed areas, the average diet underwent marked changes: fat intakes increased, meat intakes tripled between 1990 and 2021, and salt intake of 11 grams per day is among the highest in the world. As a consequence, between 1990 and 2015, heart disease almost doubled and childhood obesity reached 8.3%, one of the highest values in the world.

Conclusion

Having to feed one fifth of the world’s population gives China a very important position in the global food market. The immense changes that the country has undergone since its creation have had an impact on the way food is produced, distributed and accessed. While China is the world’s largest producer of almost all fresh food and staple grains, challenges remain around production and consumption.

On the production side, the country seeks to increase mainly self-sufficiency in soybeans and maize, feed grains that have suffered from a structural imbalance in domestic supply and demand due to the continued rapid increase in demand for protein-rich food. Due to the current geopolitical landscape, this is among the top national priorities, as mentioned by President Xi Jinping “The Chinese people must firmly hold the rice bowl in their own hands”.

In terms of consumption, China has focused on raising national awareness of conservation; advocating simple, moderate, green and low-carbon lifestyles; opposing extravagance, wastefulness and overconsumption; undertaking in-depth food-saving actions such as the “Clean Plates” campaign; and creating greener organizations, families and communities.

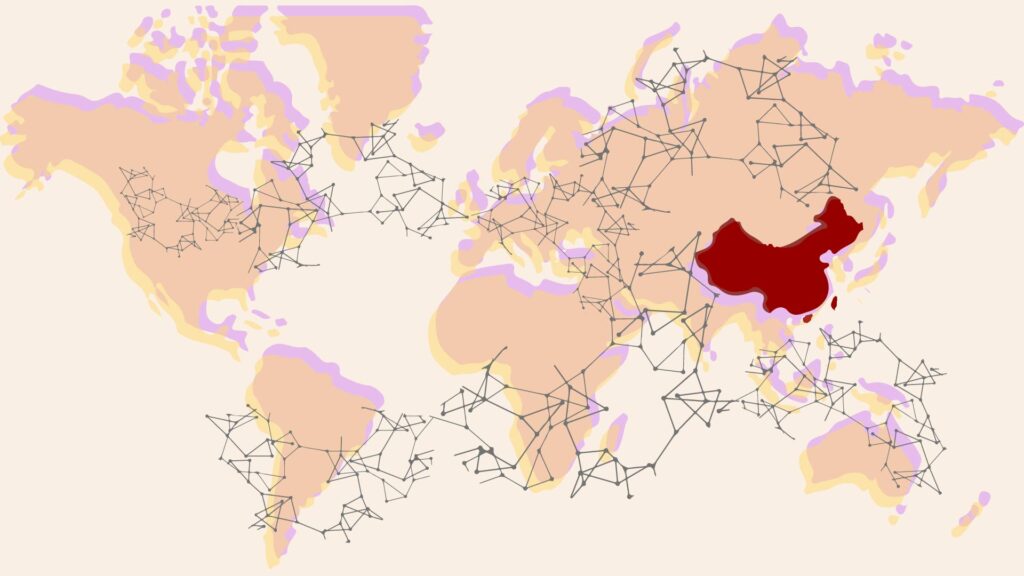

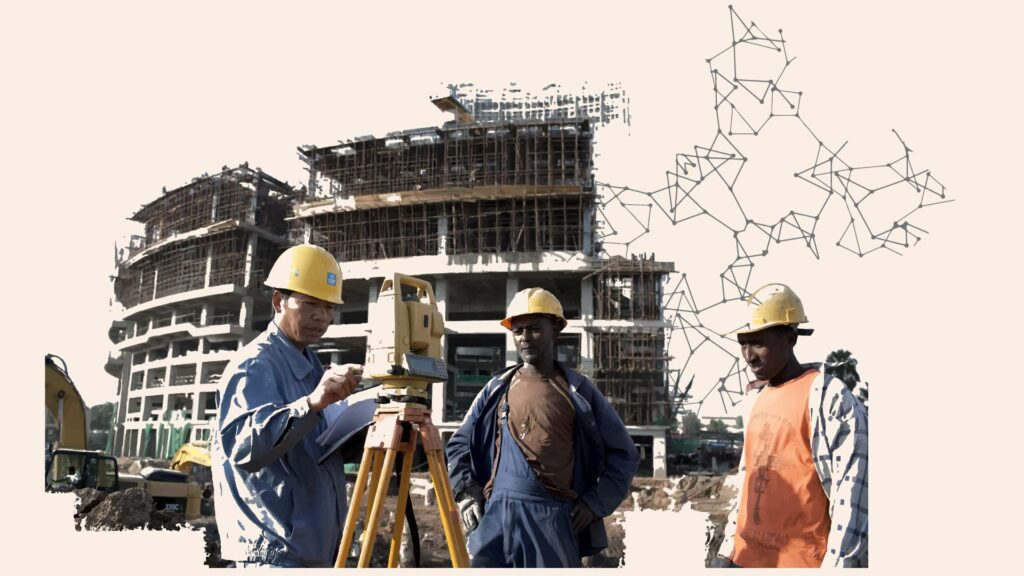

Another important contribution to the world’s population has been the definition of sharing its agricultural knowledge and technology with the world, especially among the countries of the Global South, from the sharing of heat-tolerant wheat varieties in Sudan and Yuan’s high-yielding hybrid rice in Madagascar and Liberia to the creation of key joint research institutions in Kenya and the recent commitments to cooperate on agricultural industrialization at the 15th BRICS Summit.

China’s political definition of self-sufficiency in food is a relief for the world’s population. If it were not to do so, the pressure it would put on international food prices could unbalance the market, leaving many lower-income countries in completely fragile food situations. The promotion of a modest civilization and the tradition of the majority of Chinese people to consume diets low in animal products also contributes to this.

China, with its millennia-old agricultural civilization, historical famines, management of scarce resources, elimination of extreme poverty and technical agricultural innovations, can contribute greatly to addressing the challenge of world hunger.

Subscribe. Dongsheng Explains is published monthly in English, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Follow our social media channels:

- Twitter: @DongshengNews

- Telegram: News on China

- Instagram: @DongshengNews

- YouTube: Dongsheng News

- Facebook: Dongsheng News

- TikTok: @dongshengnews