CONTENTS

PREVIOUS

China’s Foreign Exchange Reserves: Past and Present Security Challenges

‘China’s Foreign Exchange Reserves: Past and Present Security Challenges’ (中国外汇储备的前世今生和当前面临的安全挑战) was originally published in China Reform (中国改革), issue no. 4 (July 2022).

On 28 February 2022, the United States and its allies announced the freezing of $300 billion in foreign exchange reserves of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation. At that time, China’s foreign exchange reserves totalled roughly $3.3 trillion, including more than $1 trillion in US Treasury bonds.[1] The US’ weaponisation of foreign exchange reserves has forced China to re-examine the safety of its foreign exchange reserves and overseas assets.

The security of China’s foreign exchange reserves is not only an international financial issue but also a geopolitical and asset management issue. What specific measures should China take to ensure the security of its foreign reserves? To completely answer this question is beyond this author’s ability. Rather, this article only attempts to put forward a rough outline of the origin of China’s foreign exchange reserves, the challenges faced in the current period, and how to remedy the situation from the perspective of international finance.

From the Gold Standard to the Post-Bretton Woods Era

Inter-country debt is repaid through the transfer of certain internationally accepted means of settlement, such as gold, international reserve currencies, or special drawing rights (SDRs). International liquidity is the stock of these means of settlement. Countries that issue international reserve currency (i.e., the United States) can provide international liquidity or international reserves to other countries through the capital account deficit or current account deficit.[2] Under the Bretton Woods system, where the US dollar was pegged to gold, the United States provided international liquidity or international reserves for other countries through the capital account deficit. From 1945 to the beginning of the 1950s, Europe and Japan were in dire need of importing goods from the United States but were unable to obtain enough US dollars through exports and because of the severe global ‘dollar shortage’. In the 1960s, the European and Japanese economies were revitalised, and the balance of trade improved.

Meanwhile, due to the overheating of its domestic economy and its decline in international competitiveness, the US experienced a decrease in its goods trade surplus and an increase in its services trade deficit (including overseas military spending). At the same time, due to higher interest rates in Europe, US capital flowed into Europe in large quantities, bypassing controls and forming the European dollar market; the US capital account deficit increased rapidly. From the perspective of Europe and Japan, while their trade deficits were decreasing, there were still large inflows of US dollars, and so their US dollar foreign exchange reserves increased rapidly. The ‘dollar shortage’ turned into a ‘dollar glut’. From the point of view of the US, its trade surplus almost disappeared (with some countries, the US was already in a deficit), while its capital deficit increased so much that, to use the terminology of the time, the US international balance of payments deteriorated sharply.

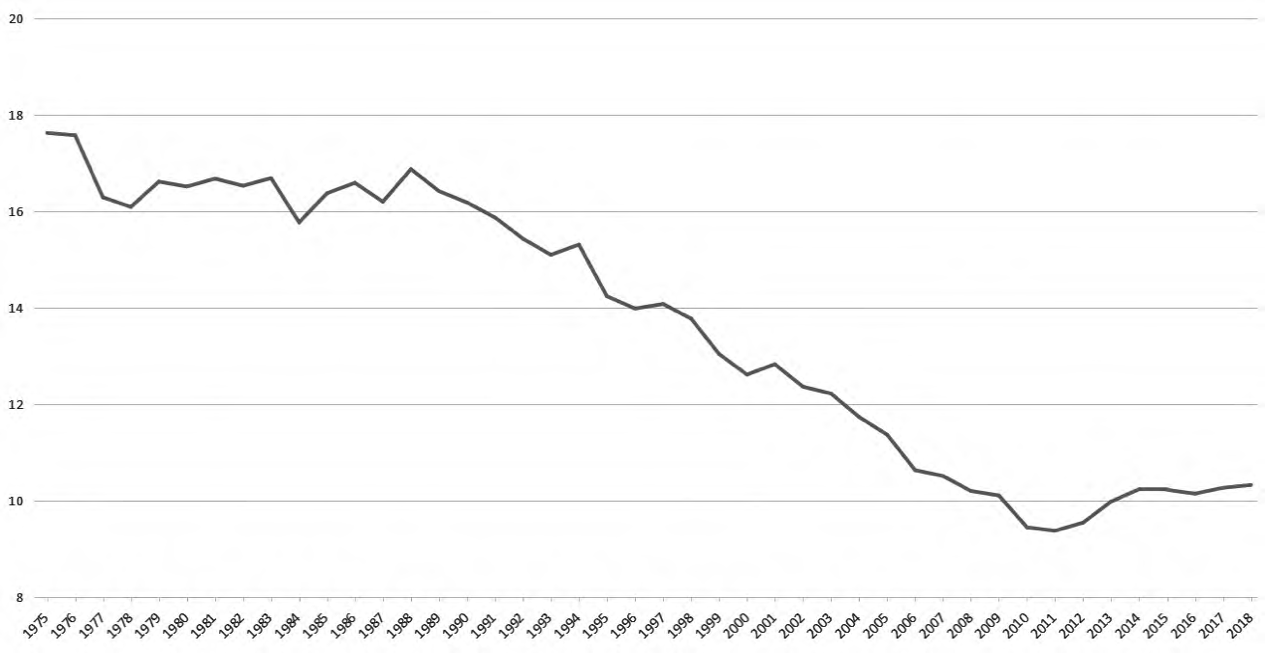

The intention behind pegging the US dollar to gold was to reassure dollar-holders that although the US dollar was a fiat currency printed by the United States with no inherent value, it could be exchanged for gold at a given rate. Thus, they could hold US dollars with trust. For the US, under the gold exchange standard, the international imbalance of payments resulted in the loss of US gold reserves. While the gold may have remained in US vaults, it was no longer owned by the US. Foreign central banks could always convert excess US dollars into gold, and ship the gold back to their countries. By 1971, the US held just over $10 billion in gold reserves, compared to the more than $40 billion and $30 billion held by foreign officials and private individuals, respectively. Eventually, the United States could no longer afford to keep the promised exchange rate of $35 per ounce of gold. On 15 August 1971, US President Richard Nixon announced the closure of the ‘gold window’. The Bretton Woods system collapsed.

However, the inherent contradiction of using a country’s fiat currency as an international reserve currency has not disappeared under the post-Bretton Woods system. As the anchor of the international monetary system, the US dollar must remain stable. This stability is multidimensional; for example, its purchasing power should be stable. On the one hand, the US dollar has to play the role of a global public good and should serve the global interest. On the other hand, the US dollar is printed by the US government. Whether the real purchasing power of the US dollar can remain stable depends fundamentally on the domestic policy of the US government, which has no obligation to sacrifice its national interests for the global public interest.

In the post-Bretton Woods era, since the United States is no longer an overwhelmingly dominant economic power, the contradiction between the US dollar’s status as a national currency (serving US interests) and its status as an international reserve currency (serving global interests) manifests itself in the fact that the US has to provide the world with international liquidity, or a reserve currency, primarily through current account deficits (trade deficits). As the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) grows, so does the international reserve currency required for global trade and financial transactions. The more reserve currency the US provides to the world, the larger the US trade deficit must be. To put it another way, the United States provides global reserve currency through IOUs. The growth of the global economy requires the US to issue more IOUs, and the more IOUs issued, the more foreign debt the US holds. However, economists did not expect that despite the US having a huge net debt, its balance of payments on investment income would be positive. Not only does the US not have to pay interest, but it also collects a lot of it. The fundamental reason why the US dollar has remained stable – even though the US is the world’s largest debtor – is that the rest of the world’s demand for the US dollar as a reserve currency has also been increasing, which means that other countries are willing to lend money to the US and are willing to finance the US trade deficit. In this way, the gap between domestic investment and savings within the United States is made up by foreign savings, and the pressure of inflation and US dollar depreciation is greatly reduced. If there had not been a strong demand for US dollar foreign exchange reserves in other countries while the US was indiscriminately issuing dollars to make up for its lack of domestic savings, the US dollar would have collapsed long ago.

Since the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008, the United States has implemented extremely expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. The strong demand for US Treasury bonds and other US assets by foreign governments and investors has created the necessary external conditions for low inflation and faster growth in the US for more than ten years. However, the US has accumulated net foreign liabilities of $14 trillion (2020) and a national debt of $28 trillion (2021), with ratios to GDP of roughly 67 percent and 122 percent, respectively.[3] The situation is only continuing to deteriorate. According to the US Congressional Budget Office, the US national debt-to-GDP ratio will surpass 200 percent by 2051.[4] The US government has acknowledged that its fiscal situation is unsustainable.

No one knows how long investor confidence in the US dollar and US Treasuries can be maintained in the face of the country’s worsening debt situation. No one knows when the market will lose confidence in the US dollar and it will collapse. But would it not be prudent to factor that possibility into decision-making?

Implications of the US Freezing Russia’s Foreign Exchange Reserves

Following the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the United States froze $300 billion in foreign exchange reserves of the Russian Central Bank within 72 hours. This has seriously undermined the international credibility of the US and shaken the credit foundation of the Western-dominated international financial system. Which country can be sure that the US will not freeze its foreign exchange reserves similarly in the future? The US’ weaponisation of foreign exchange reserves has exceeded the worst estimates of economists about the security of China’s foreign exchange reserves. The value of China’s foreign exchange reserves will not only suffer losses due to US inflation, dollar depreciation, and falling treasury bond prices or defaults but they may be wiped out instantly for geopolitical reasons.

Will the United States take such extreme actions against China’s foreign reserves? As early as 2013, Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator for the Financial Times, wrote that the US could well freeze China’s foreign exchange assets in the event of a conflict.[5] While both sides would suffer heavy losses, China’s losses would be even heavier. One question that China may soon face is whether it should join the embargo on Russian oil and gas and comprehensive financial sanctions against Russia. So far, the US has not imposed a comprehensive oil and gas embargo on Russia, and China and India are still allowed to buy Russian oil and gas. However, once the US believes that Europe can be rid of its dependence on Russian oil and gas, it may then point its finger at China and India. China’s continued purchase of Russian oil and gas will likely become a reason for the US to act against China’s foreign reserves or impose sanctions on Chinese financial institutions.

China’s Massive Foreign Exchange Reserves and Countermeasures

China has accumulated its massive foreign exchange reserves over a long period of time, through ‘double surpluses’ – current account surplus and capital account surplus. By any standard, China’s holdings of $3.3 trillion in foreign exchange reserves (excluding Hong Kong’s $496.8 billion and Taiwan’s $548.4 billion) far exceed the internationally recognised reserve adequacy requirement; the second, third, and fourth largest foreign exchange reserve holders in the world are Japan, with $1.3 trillion; Switzerland, with $1 trillion; and India, with $569.9 billion.[6] There are only three countries in the world with foreign exchange reserves of more than one trillion US dollars (China, Japan, and Switzerland), and China’s foreign exchange reserves are nearly three times that of Japan, which is ranked second.

Since the rate of return on foreign exchange reserves is extremely low, if the proportion of foreign exchange reserves in overseas assets is too high, the overall rate of return on overseas assets will inevitably be too low. Of China’s $9 trillion in overseas assets, reserve assets account for 37 percent of the total; of these reserve assets, US Treasury bills account for 32 percent.[7] It should be noted that, to improve the rate of return on foreign exchange reserves, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, an administrative body of the People’s Bank of China, and other relevant agencies have taken into account not only safety and liquidity but also the rate of return in their asset allocation. In addition to treasury bills of the United States and other countries, China’s reserve assets also include bonds of international organisations, local government bonds, private equity investments, and policy investments such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). These efforts should be productive. However, in any case, because of the safety and liquidity requirements of foreign reserves, an overproportion of foreign reserves in overseas assets will inevitably lead to lower income from overseas assets. Not only that, a large proportion of China’s foreign exchange reserves is ‘borrowed’ through the introduction of foreign capital rather than ‘earned’ through the trade surplus. Compared with the investment income of foreign reserves, the debt cost of ‘borrowed’ foreign exchange reserves is extremely high. A 2008 survey conducted by the World Bank office in Beijing showed that the investment income of US enterprises in China is 33 percent compared with 22 percent for foreign enterprises in general. At the same time, the investment return on US Treasury bills was less than 3 percent. This situation is also one of the reasons for China’s negative investment returns despite its $2 trillion in net overseas assets. China’s balance of payments and overseas investment position is in stark contrast to that of the United States. As mentioned, the latter will have nearly $200 billion in investment income in 2021 despite being a $15 trillion net debtor. Looking around the world, Argentina and Russia are the only countries in the same boat as China.

In the early days after China’s opening up, the shortage of foreign exchange was the main bottleneck to the country’s growth. Although there was partiality and overreaction, it was ultimately the right step for China to develop processing trade vigorously to earn foreign exchange, actively introducing foreign direct investment and drastically devaluing the Chinese renminbi (RMB) in one go. However, after the Asian financial turmoil in 2003, China, due to ‘appreciation phobia’, delayed the slight appreciation of the RMB until 2005. The consequence of this is that, on the one hand, China’s trade surplus increased sharply, and, on the other hand, the domestic asset bubble and the strong expectation of RMB appreciation led to a large inflow of ‘hot money’. China’s capital account surplus once exceeded the trade surplus and became the primary source of new foreign exchange reserves. It is fair to say that China’s failure to let the RMB appreciate in time and its lack of exchange rate flexibility were the conditions that led to the country’s excessive accumulation of foreign exchange reserves.

The principal purposes for restructuring China’s overseas asset-liability structure and balance of payments structure should be twofold. First, to improve the structure of China’s overseas assets-liabilities and to increase the return on its net overseas assets. To this end, China should reduce the share of foreign exchange reserves in its overseas assets. Second, to improve the safety of China’s overseas assets, especially its foreign exchange reserves. Under current conditions, China should reduce its stock of foreign exchange reserves to at least the internationally recognised level of foreign exchange reserve adequacy. How much foreign exchange reserves should a country hold? In general, this depends on the size of the country’s imports (or exports), the size of short-term foreign debt, the size of other securities liabilities, and the broader money supply (M2).[8] At the same time, it is also necessary to consider the country’s exchange rate regime and capital controls. For example, if the country has a floating exchange rate and capital controls, the country’s foreign exchange reserve adequacy ratio can be significantly reduced.

The possibility of the United States freezing and seizing China’s overseas assets cannot be ruled out. However, the greater likelihood is that the US will act against China by using its Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list to target individuals and entities with sanctions (akin to the now defunct Part 561 List sanctions against Iran). To deal with this possibility, China needs to improve its financial infrastructure. For its existing stock of foreign exchange reserves, measures that China should consider include:

1. Increasing holdings of other forms of assets while reducing US Treasuries holdings. In the past, arguments have been made in favour of currency diversification of China’s foreign exchange reserves (towards the Euro and Japanese yen) due to concerns about the depreciation of the US dollar. However, under the current geopolitical conditions, such diversification may not be sensible.

2. Accelerating the construction of financial infrastructure – such as settlement, clearing, and messaging systems – that is independent of the US. Make full use of China’s technological reserves and strength in the field of digital technology to improve the cross-border payment system that adapts to the new trend of digital trade.

3. Reducing US Treasury bills holdings in accordance with market rules. In recent years, it has been reported that central banks in many countries have been selling US Treasury bills. Such trading activities are purely commercial, so the US should have no grounds to object.

What Role Can RMB Internationalisation Play?

As the international geopolitical situation has deteriorated, RMB internationalisation has once again become a hot topic. In 2008, the US subprime mortgage crisis erupted, and the bankruptcy of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which held large amounts of US Treasury and government agency debt, caused great anxiety in the Chinese government. In 2009, Zhou Xiaochuan, then governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the country’s central bank, proposed that SDRs replace the US dollar as the international reserve currency. However, this proposal was aborted due to the opposition of the United States. So, China found another way to reduce the risk of its overseas assets: internationalising the RMB. However, the process of RMB internationalisation would be hindered as the expectation of RMB appreciation turned to depreciation. For some time after 2015, China had to tighten capital controls due to serious capital outflows and flight.

Yi Gang, who succeeded Zhou as governor of the PBOC, stressed on several occasions that ‘RMB internationalisation should be market-driven, and the central bank will not take the initiative to promote it’.[9] Governor Yi’s assertion is correct and in line with the historical experience of RMB internationalisation to date. In fact, from 2009 to 2014, detailed and thorough discussions were held on the benefits and costs of RMB internationalisation and the roadmap for China to follow in both domestic and overseas economic spheres. These ideas have since been tested in practice. For example, when China pushed for RMB import settlement in the past, the US dollar was replaced by the RMB to pay for imports when China had a large current account surplus and, as a result, China’s foreign exchange reserves in US dollars increased rather than decreased. As another example, it was hoped that non-residents would increase their holdings of RMB deposits and RMB treasury bonds in large quantities, but after the expectation of RMB appreciation disappeared in 2014, the interest of non-residents in holding RMB deposits and other RMB assets largely disappeared as well. Experience tells us that while RMB internationalisation is a worthy cause, the process must be market-driven. China should not prioritise short-term benefits or instant gratification, nor should it try to help young shoots grow by dragging them up.

Whenever possible, the buyer’s or seller’s advantage should be used to advance RMB-denominated pricing and settlement. For example, China is the largest buyer of many commodities, and it would undoubtedly benefit China if these commodities were denominated in RMB. Driven by the market, the internationalisation of the RMB has indeed made solid, if not spectacular, progress. On the whole, the RMB’s emergence as an international currency, and in particular an international reserve currency, could bring enormous benefits to China.

In general, however, RMB internationalisation should not be given priority over commercial considerations. For example, when a Chinese investor buys a foreign bond in the international capital market, the currency in which the bond is denominated and settled is determined by the market. For Chinese investors, if the RMB is on a long-term appreciation path, it is preferable for the bond to be denominated in RMB rather than US dollars; meanwhile, where a Chinese company is in a debtor position, it is preferable for the bond to be denominated and settled in a depreciating currency. China also needs to promote the internationalisation of its capital markets. However, the purpose of such promotion, especially the bond market, is not to internationalise the RMB but to improve the efficiency of China’s financial resource allocation. The market knows best what is going on at the micro level. The choice of currency in trade and financial transactions should be left to the discretion of enterprises and financial institutions. As China’s economic strength grows stronger and its financial markets become more sophisticated, the RMB will naturally be chosen more and more as the international currency of denomination and settlement.

The highest level of RMB internationalisation is for the RMB to become a reserve currency for other countries. The RMB can be supplied to other countries through current account deficits and capital account surpluses; China pays for its trade deficit in RMB, and the central bank of the country with a trade surplus acquires and holds the RMB in the foreign exchange market, using the RMB to buy Chinese treasury bonds or certain safe and liquid Chinese bonds. In this way, the RMB becomes the surplus country’s reserve currency. China, in turn, can use the RMB’s status as an international reserve currency and a credit note to gain access to resources.

China can also promote the RMB as a reserve currency through capital exports. Generally speaking, when China provides RMB to other countries through capital export, the capital-importing country will use these RMB to import goods from China and the RMB will flow back to China. The capital-importing country will record a Chinese trade deficit and an equivalent capital account surplus on its balance of payments statement, but its foreign exchange reserves will not increase as a result. If the country does not use the RMB to purchase Chinese goods, the RMB may flow out of the country through the capital account, or it may be sold to the country’s central bank and used to purchase Chinese treasury bonds or other safe and liquid financial assets, thus forming the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

However, for the recipient countries of Chinese capital exports, these RMB foreign exchange reserves would be borrowed from China, not earned through export surpluses. Importing capital from China and not using it to buy Chinese goods and services, but rather to hold short-term Chinese capital with low returns may be a misallocation of resources. As a result, the recipients of Chinese capital exports will minimise this portion of RMB foreign exchange reserves. In other words, while China may provide other countries with RMB through capital exports, the willingness of other countries to convert the corresponding RMB into Chinese short-term bonds or treasury bonds (if the latter are available) – thereby forming these countries RMB foreign exchange reserves – may be limited.

In short, for the RMB to become an international reserve currency, China must fulfil a series of preconditions, including establishing a sound capital market (especially a deep and highly liquid treasury bond market), a flexible exchange rate regime, free cross-border capital flows, and long-term credit in the market. In short, China must overcome the so-called ‘original sin’ in international finance and be able to issue treasury bonds internationally in RMB.[10] Otherwise, it will be difficult for the RMB to become an international reserve currency and RMB internationalisation will remain incomplete.

Can RMB internationalisation enhance the security of China’s foreign exchange reserves? If this question is considered in the context of a complex global economic system, the answer should be yes. However, in the short term and in terms of direct impact, even if China’s foreign exchange reserves consisted entirely of RMB assets, their security would not change substantially. There are more than $1 trillion worth of US Treasury bills among China’s foreign exchange reserves. If the United States does not intend to repay the principal and interest according to the original agreement, what can China do? Nothing. Suppose the US Treasury issues 7 trillion RMB in treasury bonds and China owns 7 trillion RMB instead of $1 trillion in foreign exchange reserves by buying this US-issued RMB bond; if the US does not intend to make debt service payments on US Treasuries that are agreed to be denominated in RMB, the dilemma that China faces will remain the same as if the assets are denominated in US dollars. Because the key to the problem does not lie in the currency that China’s foreign exchange reserves are denominated and settled in, but in whether China owes the United States money or vice versa. Regardless of their denomination and settlement, China’s foreign exchange reserves are US debt to China. It is money that the US owes China. Thus, the safety of China’s foreign exchange reserves depends on whether the US will honour its debt-servicing commitments and, should it not, whether China can compel the US to do so. If China cannot ensure that the US will not renege, it has no choice but to gradually reduce its foreign exchange reserves. Of course, denominating and settling certain transactions (e.g., imports) in RMB can lead to a reduction in foreign exchange reserves, thus strengthening the security of China’s foreign reserves in an indirect sense. It is interesting to note that in early December 1950, when the US announced a severe ‘blockade’ and ‘embargo’ against China, China endeavoured to ‘snatch’ and ‘buy’ goods from Western countries. By the time the United Nations passed the embargo resolution against China in 1951, China had used up all its foreign exchange savings.

In short, while RMB internationalisation is a goal worth pursuing, it is a long-term process; distant water will not quench immediate thirst. In the face of geopolitical challenges, RMB internationalisation will also have a limited effect in protecting China’s existing overseas assets.

What China can now do to address the challenges with its foreign exchange reserves is to ‘mend the fold’; in other words, it is better to act late than never. As one of China’s greatest poets, Tao Yuanming (365–427 CE), wrote, ‘Knowing that what I did in the past cannot be redressed, I can still retrieve my mistakes in the future’. The key is to properly understand and implement the strategic policy of fostering a new development paradigm with domestic circulation as the foundation and domestic and international circulation reinforcing each other. Doing so will accelerate the transformation of China’s development strategy, realise the turn towards domestic circulation, and consolidate domestic demand as the driving force of economic growth.

The British economist John Maynard Keynes once said, ‘If you owe your bank a hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe a million, it has’. In the current perilous geopolitical environment, if a country cannot safeguard its rights as a creditor, it should strive to avoid becoming a creditor as much as possible. In the face of potential US financial sanctions in the near future, China’s decision-making authorities must analyse various possible scenarios and develop preventive and responsive countermeasures.

Bibliography

‘2021 Annual Report’. Beijing: State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.safe.gov.cn/en/2020/1221/2163.html.

‘2021 Financial Report of the United States Government’. Washington, DC: US Department of the Treasury, February 2022. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/2021-FRUSG-FINAL-220217.pdf.

Eichengreen, Barry, and Ricardo Hausmann. ‘Exchange Rates and Financial Fragility’. NBER Working Paper 7418. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, November 1999. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w7418/w7418.pdf.

‘Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities’. Washington, DC: US Department of the Treasury, 15 March 2023. https://ticdata.treasury.gov/Publish/mfh.txt.

Milesi-Ferretti, Gian Maria. ‘The US Is Increasingly a Net Debtor Nation. Should We Worry?’ The Brookings Institution, 14 April 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-us-is-increasingly-a-net-debtor-nation-should-we-worry/.

‘The 2021 Long-Term Budget Outlook’. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, March 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57038.

Wolf, Martin. ‘China Must Not Copy the Kaiser’s Errors’. Financial Times, 3 December 2013. https://www.ft.com/content/672d7028-5b83-11e3-a2ba-00144feabdc0.

‘人民银行副行长易纲:人民币国际化应由市场驱动’ [Yi Gang, Vice Governor of the People’s Bank of China: RMB Internationalisation Should Be Driven by the Market]. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 14 October 2012. https://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-10/14/content_2242995.htm.

Author’s Notes

1. See ‘2021 Annual Report’ (Beijing: State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People’s Republic of China), https://www.safe.gov.cn/en/2020/1221/2163.html; ‘Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities’ (Washington, DC: US Department of the Treasury, 15 March 2023), https://ticdata.treasury.gov/Publish/mfh.txt. ↑

2. In international macroeconomics, the balance of payments records all transactions made between entities in one country with entities in the rest of the world. These transactions consist of imports and exports of goods, services, capital, and transfer payments such as foreign aid and remittances. A capital account deficit shows that more money is flowing out of the economy along with an increase in its ownership of foreign assets. The current account is defined as the sum of the balance of trade (goods and services exports minus imports), net income from abroad, and net current transfers. A current account deficit occurs when the total value of goods and services a country imports exceeds the total value of goods and services it exports. ↑

3. On US net foreign liabilities, see Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, ‘The US Is Increasingly a Net Debtor Nation. Should We Worry?’, The Brookings Institution, 14 April 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-us-is-increasingly-a-net-debtor-nation-should-we-worry/. On US national debt, see ‘2021 Financial Report of the United States Government’ (Washington, DC: US Department of the Treasury, February 2022), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/2021-FRUSG-FINAL-220217.pdf. ↑

4. ‘The 2021 Long-Term Budget Outlook’ (Washington, DC: US Congressional Budget Office, March 2021), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57038. ↑

5. Martin Wolf, ‘China Must Not Copy the Kaiser’s Errors’, Financial Times, 3 December 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/672d7028-5b83-11e3-a2ba-00144feabdc0. ↑

6. Foreign exchange reserves as of the end of 2021. Sources: State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Taiwan’s central bank, Japanese Ministry of Finance, Swiss National Bank, Reserve Bank of India. ↑

7. ‘2021 Annual Report’ (Beijing: State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People’s Republic of China), https://www.safe.gov.cn/en/2020/1221/2163.html. ↑

8. Several measures are used to gauge the money supply (i.e., the total amount of money in circulation) in an economy. The World Bank defines these measures as follows: ‘The narrowest, M1, encompasses currency held by the public and demand deposits with banks. M2 includes M1 plus time and savings deposits with banks that require prior notice for withdrawal. M3 includes M2 as well as various money market instruments, such as certificates of deposit issued by banks, bank deposits denominated in foreign currency, and deposits with financial institutions other than banks.’ See ‘Metadata Glossary’, The World Bank, accessed 20 March 2024, https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/world-development-indicators/series/FM.LBL.BMNY.ZG. ↑

9. ‘人民银行副行长易纲:人民币国际化应由市场驱动’ [Yi Gang, Vice Governor of the People’s Bank of China: RMB Internationalisation Should Be Driven by the Market], The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 14 October 2012, https://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-10/14/content_2242995.htm. ↑

10. In international financial literature, ‘original sin’ is a term that refers to ‘a situation in which the domestic currency cannot be used to borrow abroad or to borrow long term, even domestically’. See Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Hausmann, ‘Exchange Rates and Financial Fragility’, NBER Working Paper 7418 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, November 1999), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w7418/w7418.pdf. ↑